Greetings plankton enthusiasts, new and old! My name is Jenna Binstein and I recently graduated from undergrad at the University of Miami. I enjoyed my time there so much though, that I signed on for another year as a graduate student! Part of what made my undergraduate years so fulfilling and worthwhile was my work in the lab with Dr. Cowen, Jessica, and the rest of the ISIIS/plankton team. Before I go into more detail about my work there, let’s take a quick look at how I found my way into the marine sciences.

It all started when I got my SCUBA certification as a freshman in high school. After my first open water dive I was hooked. I knew I had to learn all there was to know about marine science. At first, I thought I wanted to study the “big” stuff: dolphins, sharks, or turtles. I had seen jellyfish on SCUBA dives before, but I always considered them pests. I never thought as I applied and enrolled at UM that I would find such passion in studying some of the smallest organisms in the ocean, and learn just how important and collectively “big” they actually are.

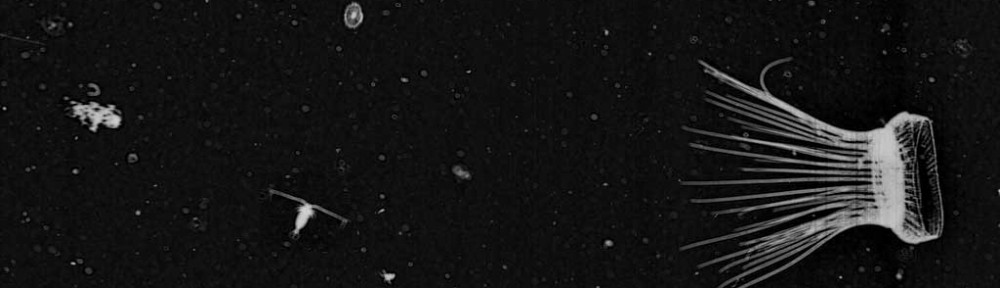

Basically, my journey with plankton started when I met Jessica and Adam and began helping them with their respective dissertation research. I started learning to identify zooplankton, just as you all are learning to do via Plankton Portal! I started getting comfortable with the images from ISIIS, and eventually began to develop my own interest and senior thesis project with mentorship from Jessica. I decided to begin looking more closely at Appendicularians. Very little is known about these guys and their unusual mucous housing. So I spent a long time quantifying Appendiularians by size, classification, and whether or not they were inside a mucous housing when I saw them. The goal was to be able to identify an existing relationship between depth and whether or not an Appendicularian was found in its housing. I briefly looked at other factors as well, such as frontal dynamics, size, and classification and then saw if these related to an Appendicularian being in or out of its house. Although I completed my senior thesis, the work is not over; as there is still so much more I can pull from the data! Yet overall, I learned so much about Appendicularians and their role in the oceans, and I will definitely share as much of that as I can with all of you on some later blog posts relating specifically to the Appendicularian. In the meantime, I hope to continue learning all I can about Appendicularians and other gelatinous zooplankton during my time with the help of ISIIS, Plankton Portal, and UM.

Until my next post, happy jellyfishing everyone ≡≡D

Jenna Binstein, B.S.M.A.S., is a student in the Masters of Professional Science program at the Rosenstiel School of Marine and Atmospheric Sciences (RMSAS), University of Miami. You can reach her at jbinstein [at] rsmas.miami.edu.