Moritz S Schmid* and Margaret E Martinez

* schmidm@oregonstate.edu

The northern California Current (NCC) is a dynamic, highly productive region within the broader California Current Large Marine Ecosystem (CCLME), that exhibits strong ecosystem variability on seasonal, interannual, and decadal time scales. Along the California, Oregon, and Washington coasts, wind blowing alongshore the US coast can create upwelling and downwelling events. Wind blowing Southward pushes surface water away at a 90-degree angle (through the Coriolis force, see more info here). Surface waters moving away are then replaced by the deeper water underneath. This deeper water coming to the surface has more nutrients than the surface water (because the nutrient-using phytoplankton doesn’t grow as good at depth – without sunlight), and thus this upwelled, nutrient-rich water can now sustain new phytoplankton growth, which in turn can then support more zooplankton growth, and so on. Downwelling on the other hand occurs when the alongshore wind is blowing Northward. The same Coriolis effect now pushes water into the landmass at a 90-degree angle from the Northward blowing wind. Because the water has nowhere to go, the least resistance for the water is to push downward. Thus, surface water is forced deeper, and no upwelling effect occurs. Along the CA, OR, and WA coasts, wind patterns differ, and while most of the California coast experiences Southward blowing winds year-round, and subsequent upwelling also occurring year-round, Oregon and Washington experience a mix of North-, and Southward winds in summer, and predominantly Northward winds winter. The mix of South-, and Northward wind means the coast gets some upwelling and some downwelling, also referred to as intermittent upwelling, while Northward winds in winter mean that the coast gets less new nutrients from depth during that time. Ultimately, this means that the California coast experiences continuous new nutrient input from deep water that can be used by the organisms, while along the OR and WA coasts this input is more inconsistent. Nonetheless, also OR and WA coastal waters provide a unique and productive environment for plankton and fishes that sustains the livelihood of many communities on the Pacific Northwest coast.

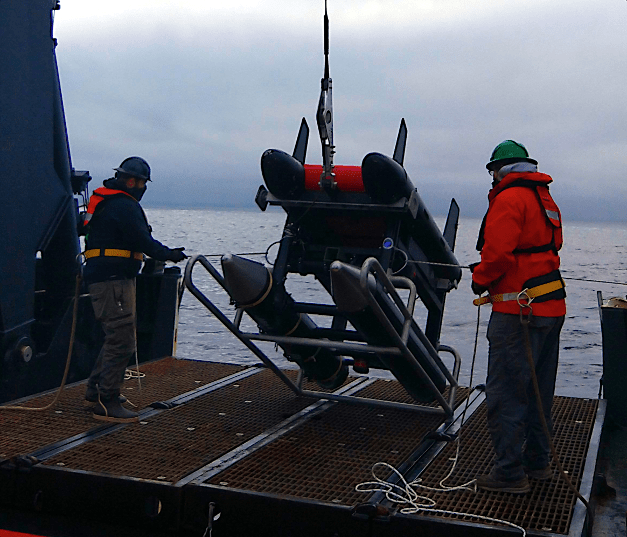

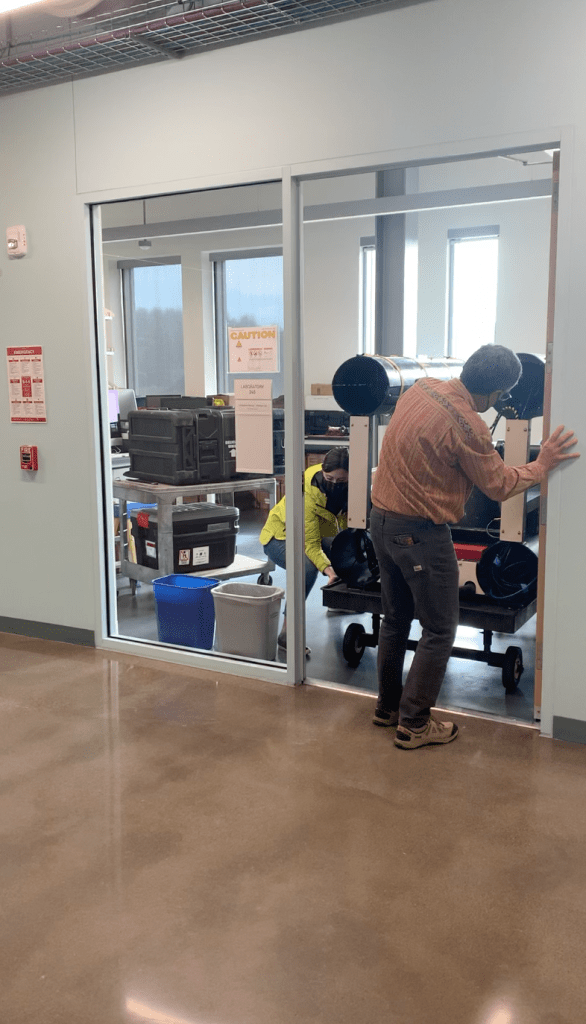

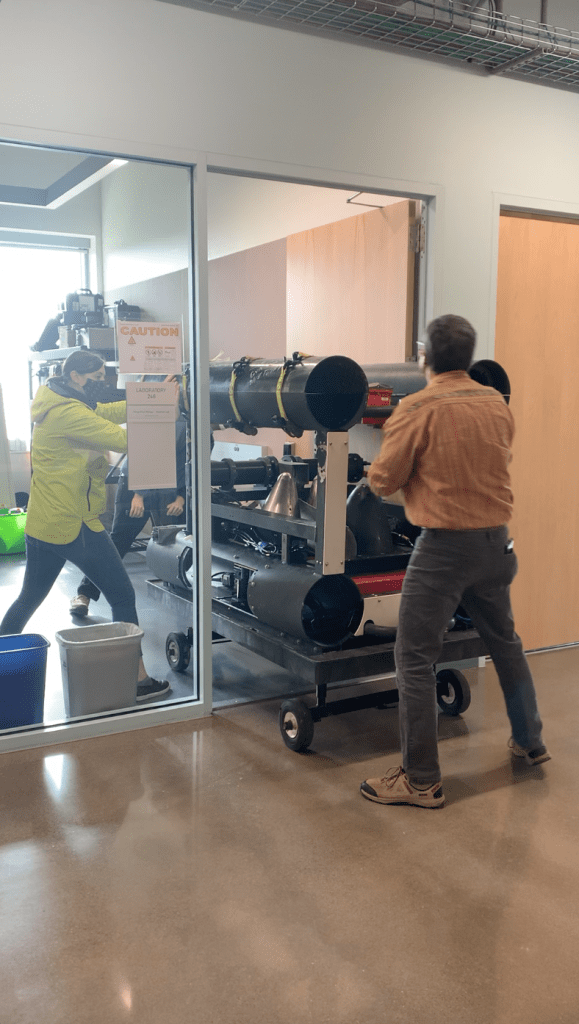

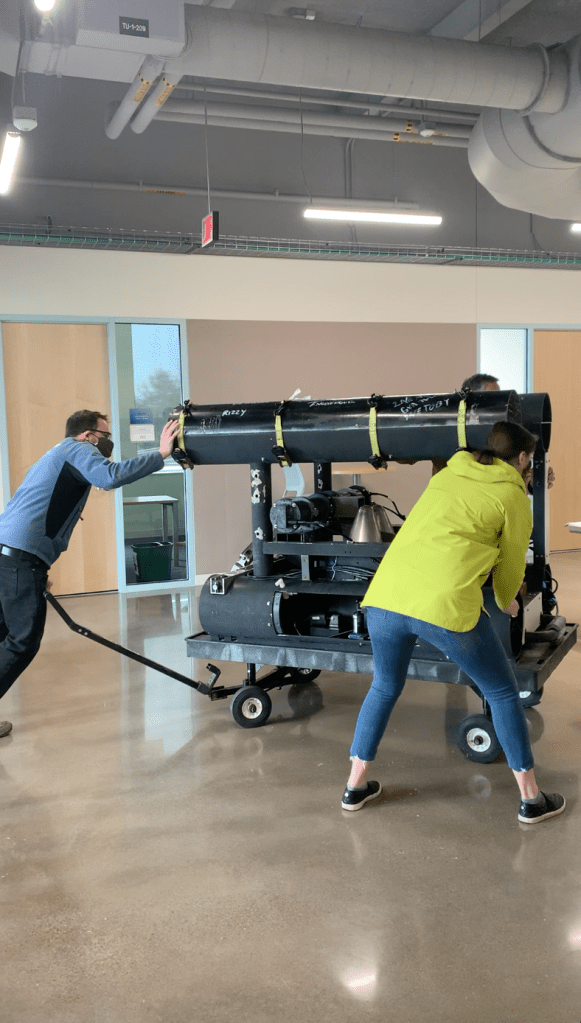

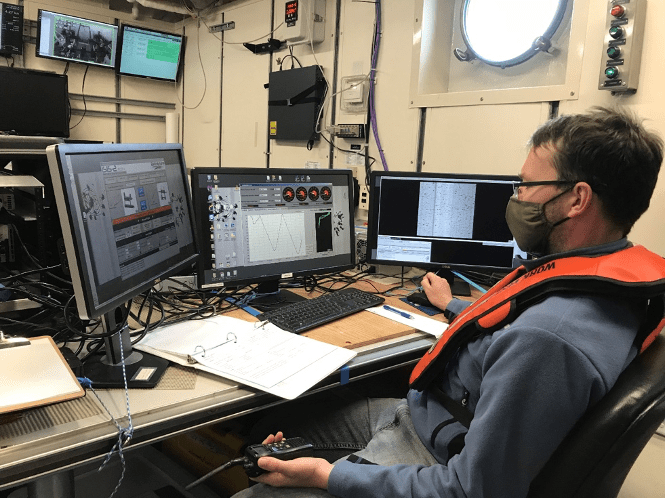

In May and early June 2021, we joined the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration’s (NOAA) Northern California Current (NCC) cruise aboard NOAAS Bell M. Shimada. NOAA’s NCC cruises occur on a regular basis and are designed to characterize the planktonic ecosystem ranging from northern California to Washington, with a focus on the Newport Hydrographic Line. Our aim was to collect zooplankton imagery for the NCC Marine Biodiversity Observation Network (MBON, see more info here and here) funded by NASA, as well as the Belmont Forum-funded project ‘World Wide Web of Plankton Image Curation’ (wPIC, see more info here and here), using the In Situ Ichthyoplankton Imaging System (ISIIS, Figs. 1-4).

The MBON project’s focus is on seascapes. Similar to different landscapes on land, the surface ocean can be classified into different categories based on environmental variables such as phytoplankton abundance and temperature. While seascapes are currently classified using data from the surface ocean (i.e., the first 10 m of the ocean) largely due to heavily relying on satellite data, we collect data using ISIIS to inform seascapes also using information from deeper waters (e.g., data on plankton and temperature down to 100 m). wPIC is aiming at very different things – it is largely a project focused on underwater imaging methods. The idea is that all around the world laboratories use different instruments for imaging aquatic animals, and these instruments also come with different methodologies of processing the images and ancillary data. wPIC’s aim is to streamline these efforts more and to better exploit synergies between different projects and instruments. wPIC includes project partners from France, Japan, Brazil, and the US.

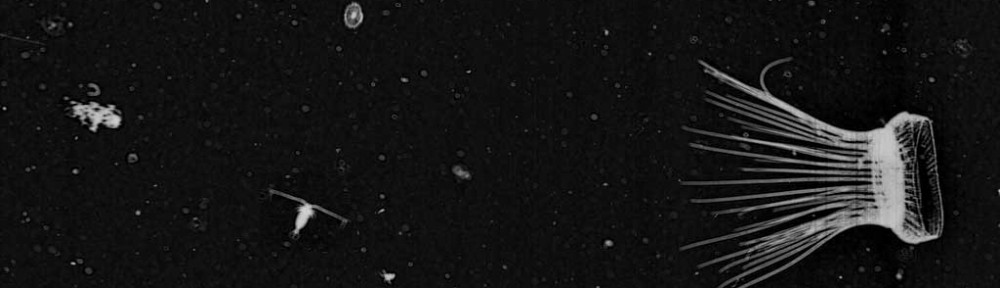

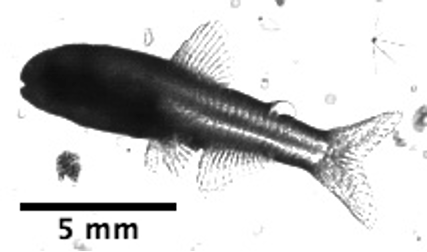

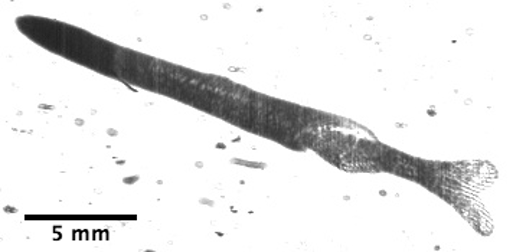

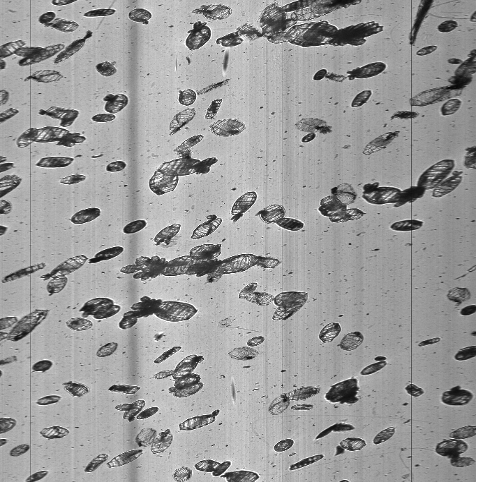

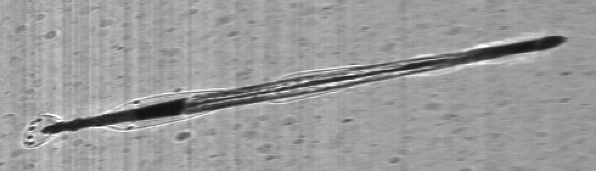

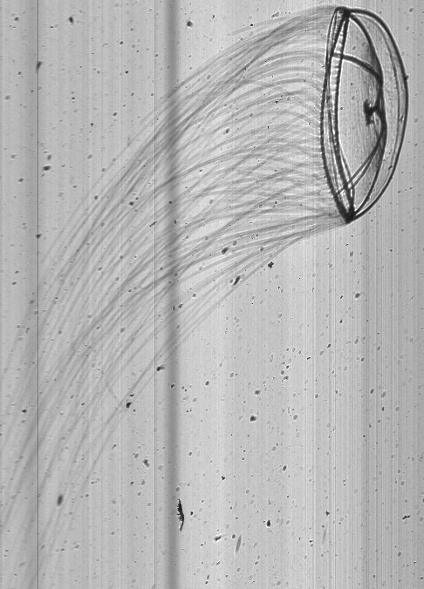

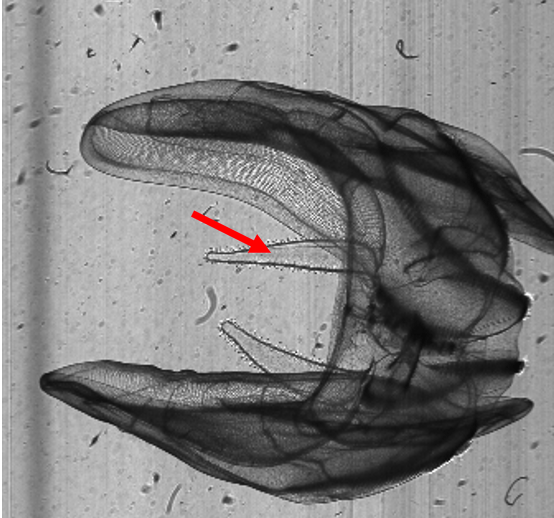

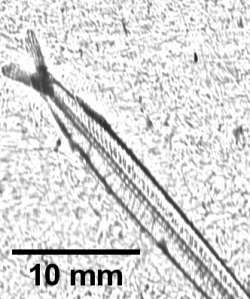

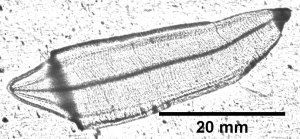

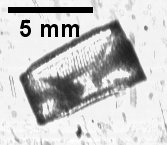

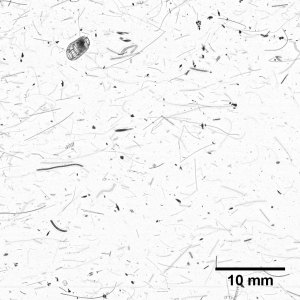

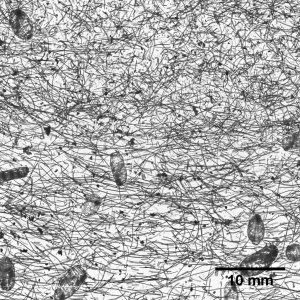

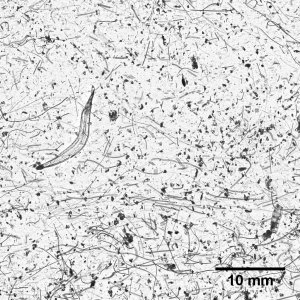

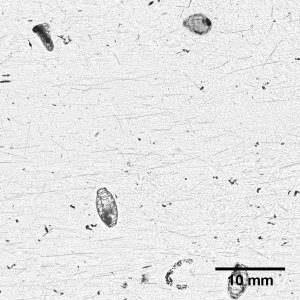

ISIIS is a line-scan and shadowgraph imager that records the shadows of organisms swimming through the beam of light projected by a LED (Fig. 5). With this setup, a water parcel measuring 13 cm x 13 cm x 45 cm is recorded by the camera system, ultimately leading to 180 L of seawater imaged per second. Compared to other imaging systems, this is a very large volume of imaged water, which gives us the ability to look at rather rare larval fishes (Fig. 6) as well as fragile jellies and the ubiquitous crustacean zooplankton (Figs 7-8).

— Figure 6. A myctophid (lanternfish, left), and an engrauliid (anchovy, right).

_________________________________________________________________________________

_________________________________________________________________________________

— Figure 7. Key gelatinous zooplankton in the NCC includes doliolids, chaetognaths, ctenophores, and hydromedusae*.

_________________________________________________________________________________

_________________________________________________________________________________

— Figure 8. Key crustaceans include euphausiids and calanoid copepods. ISIIS’s ability to image fragile jellyfish without disturbance is clearly visible in the images of Mitrocoma and its many tentacles, as well as a ctenophore with its auricles clearly visible*.

*All images except the doliolids (Crescent City line, 5/26/2021), were taken from Newport Hydrographic Line imagery (5/23/2021).

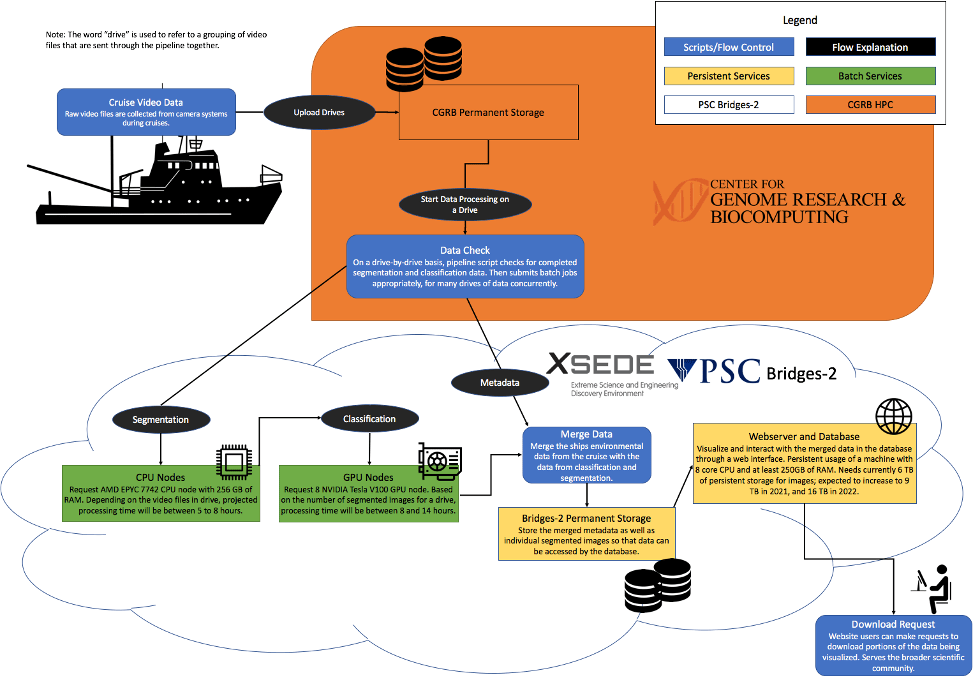

Using a sophisticated image processing pipeline (Luo et al. 2018, Schmid et al. 2021), based on artificial intelligence, we can quickly identify all plankton in the images, and also get their sizes. These ecological data can then be used in a diversity of ecological studies. As ISIIS produces vast quantities of data (ca. 75-100 million images for a 7-hr ISIIS transect) we collaborate with the National Science Foundation’s Extreme Science and Engineering Discovery Environment (XSEDE), a nationwide supercomputing cluster. Controlling the processing from Oregon State University’s (OSU) Center for Genomics and Biocomputing (CGRB), but utilizing hardware at XSEDE (Fig. 9), we are able to get through the data blazingly fast. The resulting data enables us to tackle ecological questions that wouldn’t be possible with more traditional net systems (e.g., Briseño-Avena et al. 2020, Schmid et al. 2020, Swieca et al. 2020).

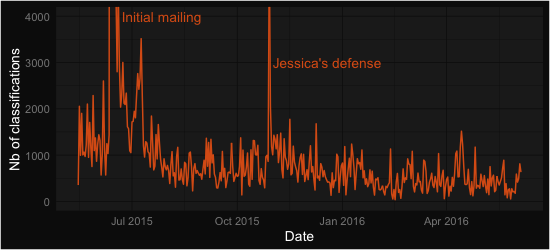

At this point we want to give a big shout out to all our citizen scientists at Plankton Portal who help with making these studies possible by volunteering to classify plankton. This effort helps us to fine-tune plankton classification image libraries and models, and provides insight into how automated plankton classifications differ from human annotations (Robinson et al. 2017). We hope that you enjoyed this little glimpse into collecting the images that you get to look at. We also thank Jennifer Fisher, the Chief Scientist on NOAA’s NCC cruise on NOAAS Bell M. Shimada, as well as Bell M. Shimada’s CO Amanda Goeller, and crew, as well as all scientists who helped with manning the ISIIS winch.

References:

Briseño-Avena C, Schmid M, Swieca K, Sponaugle S, Brodeur R, Cowen RK. 2020. Three dimensional cross-shelf zooplankton distributions off the central Oregon coast during anomalous oceanographic conditions. Progr Oceanogr 188:102436 https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pocean.2020.102436

Luo JY, Irisson J-O, Graham B, Guigand C, Sarafraz A, Mader C, Cowen RK. 2018. Automated plankton image analysis using convolutional neural networks. Limnol Oceanogr Methods 16: 814-827 https://doi.org/10.1002/lom3.10285

Robinson KL, Luo JY, Sponaugle S, Guigand C, Cowen RK. 2017. A tale of two crowds: Public engagement in plankton classification. Frontiers Mar Sci 4:82 https://doi.org/10.3389/fmars.2017.00082

Swieca K, Sponaugle S, Briseño-Avena C, Schmid M, Brodeur R, Cowen RK. 2020. Changing with the tides: fine-scale larval fish prey availability and predation pressure near a tidally-modulated river plume. Mar Ecol Progr Ser 650:217-238 https://doi.org/10.3354/meps13367

Schmid MS, Daprano D, Jacobson KM, Sullivan CM, Briseño-Avena C, Luo JY, Cowen RK. 2021. A Convolutional Neural Network based high-throughput image classification pipeline – code and documentation to process plankton underwater imagery using local HPC infrastructure and NSF’s XSEDE. [Software]. Zenodo. http://dx.doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.4641158

Schmid MS, Cowen RK, Robinson KL, Luo JL, Briseño-Avena C, Sponaugle S. 2020. Prey and predator overlap at the edge of a mesoscale eddy: fine-scale, in-situ distributions to inform our understanding of oceanographic processes. Sci Rep 10:921 https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-020-57879-x