We are at the end of week 2 and we pulled out some of the best finds from this past week. As a reminder, every Friday we will post a selection of Fantastic Finds. If you think you have found something really great on Plankton Portal then tag #FFF and we will check it out for use on the blog. Thanks for tagging your favorites this week!

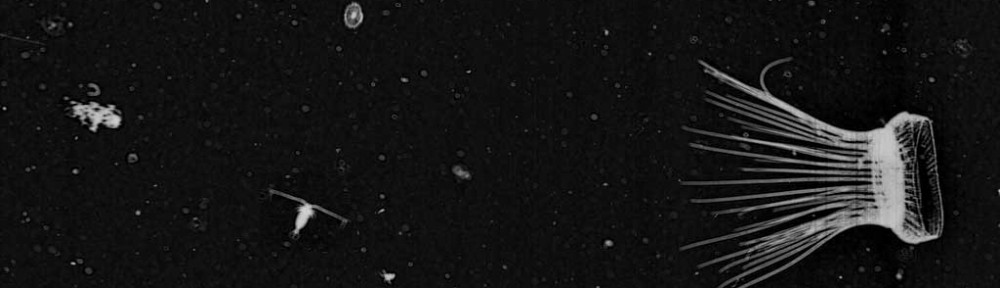

Larval fish

http://talk.planktonportal.org/#/subjects/APK00015nq

Larval fish are actually considered part of the plankton, as fish in their early life stages will drift along in the oceanic environment. Because larval fish are relatively poor swimmers, they are under high predation pressure and more than 99% of baby fish that hatch from eggs will not make it! It’s a tough life. You might not know it from this site, but studying larval fish is a major component of our lab. Dr. Cowen has spent his career studying larval fish, their distributions, dispersal and population connectivity. In this particular study, we did not sample very many larval fish so we did not include it as one of the categories. However, we are incredibly interested whenever we see one so definitely tag the fish in the forum when you see any! #Larval #fish

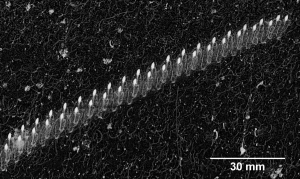

Liriope tetraphylla (#Medusae #4tentacles) with Arrow worm

http://talk.planktonportal.org/#/subjects/APK0000q5x

This is one of my favorite pictures from this week because what you see Liriope tetraphylla actually eating the arrow worm! Here one of his tentacles has brought up the arrow worm into the gastric peduncle (that’s the long thin appendage in the middle of the umbrella that looks like a handle). He appears to be holding the arrow worm in place while he eats his dinner. As far as I know, the only scientific study of what Liriope eats is from a paper by Larry Madin in 1988, published in the Bulletin of Marine Science, where he found that Liriope eats larvaceans, crustacean larvae, heteropods and juvenile fish. No one has reported that Liriope also eats arrow worms … until now.

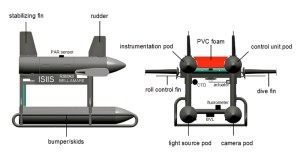

Sphaeronectes koellikeri – #rocketship #thimble

http://talk.planktonportal.org/#/subjects/APK00002cl

This beautiful creature falls within the broad group of jellyfish-relatives called the Siphonophores. Here you see this animal in a stunning feeding display. Though these guys are small and relatively inconspicuous, other siphonophores can get up to hundreds of feet long, and as a group are considered the deadliest predators in the ocean. One fun fact: these rocketship siphonophores grow from the base of the stem towards the tail end. So the tail end of the stem is one of the oldest parts of the body. Sometimes you’ll even see small rocketships budding from the tail!

Radiolarian colony – #radiolarian #colony

http://talk.planktonportal.org/#/subjects/APK00003kq

We know that you’ve been frustrated by those small fuzzy round objects that invite classification but really aren’t supposed to be classified. Those are protists, a diverse group of eukaryotic microorganisms. One type of protist is the radiolarian, which are known for their glass-like exoskeleton, or “tests.” They are incredibly important in marine science because their tests are made of silica, which are preserved in marine sediments after they die and sink to the bottom of the ocean, and provide a record for paleo-oceanographic conditions, such as temperature, water circulation, and overall climate.

Radiolarians also form colonies. Colonial radiolarians are interesting because first, little is known about them, despite their abundance in the open ocean, and secondly, they are hosts to symbiotic algae that are modest but significant primary producers in the ocean. It has also been suggested that we are vastly underestimating the abundance of radiolarian colonies. Since primary production (photosynthesis, the conversion of sun energy into carbon) is the basis upon which all ocean life can exist, it’s incredibly important to understand who all the different primary producers are and how many of them are out there!

That’s all, folks. Thanks for reading, thanks for classifying, and remember: mark your favorites with #FFF for next week’s Fantastic Finds Friday!